Remembering Private James Colk of Fromelles and the Bentleigh RSL

To mark the 109th anniversary of the Battle of Fromelles, RSL Victoria’s Communications Advisor Steven Baras-Miller reflects on his family’s connection, the effects of that experience and the role the RSL has played ever since.

When my great grandfather, James Colk, was in his 80s my family had a yearly ritual. On the Sunday before Christmas, we would spend two hours with him in his two-bedroom Ormond villa. The visit was squeezed in between seeing Great Aunt Stella in North Melbourne and my father’s parents in Jordanville.

We would sit in his loungeroom, and he would tell the same stories every year.

Mostly it was about the First World War.

The film Gallipoli had immortalised the battle, so just knowing that he had been present at one of the most famous moments in Australian history, gave him something of an aura. It made him the closest thing my family had to a legend.

But Gallipoli was not the battle he reflected on. Most of the fighting was over when he arrived there in October 1915. What he remembered about the war was a battle somewhere in France, though exactly where he never said and I am not sure he even knew.

In his memory it was the night when one thousand of his division, his mates, went into battle and there were “only 106 left at roll call the next day.” He would say this statistic every year, as if it was a fact that never left his mind.

That statistic summed up the devastation to which he had been witness. It was the losses incurred by the 60th battalion at Fromelles, France, on 19 July 1916. For him it was the moment which best represented the horrors of the First World War.

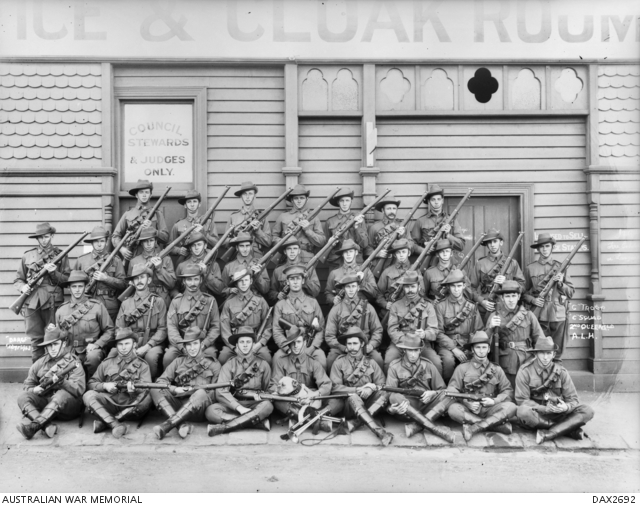

The 60th battalion suffered 757 casualties in a single night at Fromelles. Mostly they were evacuees from Gallipoli, escaping the horror there only to be cut down in their first engagement in France. The casualty number does not tell the story of every individual who went over the wall at 7 o’clock on that summers night and were gone by morning. They were defined by their absence only – not among the 106 at roll call.

For some, that absence would last almost 100 years. Buried in mass graves by the Germans in nearby Pheasant Wood, they would be anonymous and unknown until the work of a determined group of researchers led to their graves being uncovered in 2009. In the process the name Fromelles became synonymous in Australia with the horror of war.

My great grandfather was not amongst the bodies in Pheasant Wood.

He had gone over the wall and made it only about twenty metres when he was cut down by machine gun fire. It blasted off part of his shoulder and lodged bullets in his neck that would stay there for the rest of his life. They were still embedded dangerously close to his neckbone as he lay on his death bed at the repatriation hospital in Heidelberg when he was 91 years old in 1988.

The bullets had knocked him out and he woke in darkness in no man’s land, unsure where the Australian trenches were. He only knew that one way led to death and the other way home.

He stood up and blindly took several steps in the direction that felt right. He could barely walk and knew that his arm was barely attached to his body. Suddenly he heard a voice behind him, an unmistakable Australian accent calling out. “This way.”

He had been going the wrong way, heading towards the German trenches that the grand assault of the 60th had failed to overcome.

He stopped, turned, and staggered into the home trenches and, with that, his grand adventure was over. His injuries were too severe for him to continue the fight and once he had sufficiently recovered, he would see out the war years as an orderly in an English hospital. His arm was saved but his mind would take longer to heal.

He would live for another 72 years but was never the same. The battle had transformed him in ways you can only understand if you know who he was before the war.

Pa Jim, as I knew him, had a background like most of my family. They lived in slums on the outskirts of the city, around Collingwood, Richmond and Carlton. Those who were not descended from convicts became the prisoners of this new world, committing crimes of poverty and alcoholism.

Pa Jim’s wife, who he met and married after the war, was not from that world. She was middle class and from a ‘respectable’ family and considered herself an English lady who spoke of Britain as home. She fell in love with and married Pa Jim, the tall and heroic figure of the already growing ANZAC legend. But when she learnt of his upbringing, she forbade him from talking about his past.

But family secrets cannot stay buried forever.

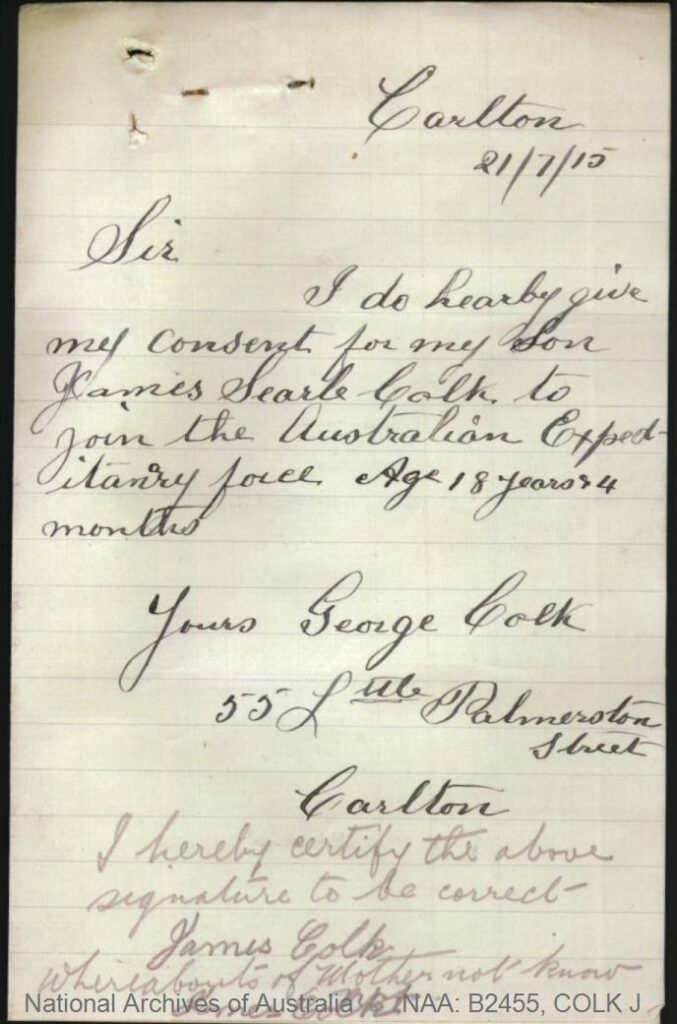

Pa Jim was born in 1897 to George Colk and Josephine McLean in Richmond. His parents married in 1888 when Josephine was 18 years old and they had their first child, a girl, in 1890.

Their life was typical of the chaos, alcohol and squalor of inner Melbourne slums of the 1890s. In 1892 Josephine was caught up in a coronial inquest into the death of her mother, Dimisha Burrows.

Somehow Dimisha had ingested poison, but Josephine did not go for a doctor because Dimisha had “been similarly unwell many times before.” The reality was that she was so often drunk that her own daughter could not tell when she drunk and when she was dying.

Pa Jim would know little of his mother who inherited her mother’s alcoholism. When he was two his nine-year-old sister died and was buried in an unmarked grave. Grief for the loss of her daughter further fuelled his mother’s alcohol addiction and, heavily intoxicated, she was arrested for attempted suicide after leaving a note that she was “going to the Yarra.”

Her marriage to George Colk fell apart completely and she abandoned him and the infant James. She fled to New South Wales where she would later be arrested for bigamy, not having divorced George before attempting to remarry in 1906.

Pa Jim was then raised by a single father in dire poverty, moving frequently from slum to slum. Such was the past that Pa Jim was not allowed to discuss.

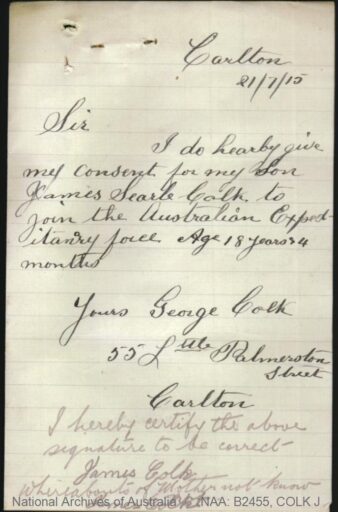

It is not surprising that James enlisted at the first opportunity in July 1915, weeks before the battle of Lone Pine at Gallipoli. He had just turned 18 and needed a letter from his father to enlist but the army offered the chance of an adventure and escape from a life of grim poverty in inner city Melbourne.

The dreams of adventure of course would end in the blood and mud of Fromelles where, but for a keen-sighted mate, he would have lain unknown for 100 years.

But Fromelles, and the war, had transformed him. He was no longer the grandson of an alcoholic mother who abandoned him and his father to commit bigamy. He was now the embodiment of the ANZAC legend. It was how he, and the rest of the world, would define him forever.

The change in Pa Jim was mirrored by the change in Australia. It had gone from the home of convicts to the land of the ANZAC.

The price Australia, and the survivors of Fromelles, would pay was a heavy one. For Australia, the cost was thousands of young men’s lives – the lost potential of them all. For the survivors like Pa Jim the price was psychological and physical trauma that would last a lifetime.

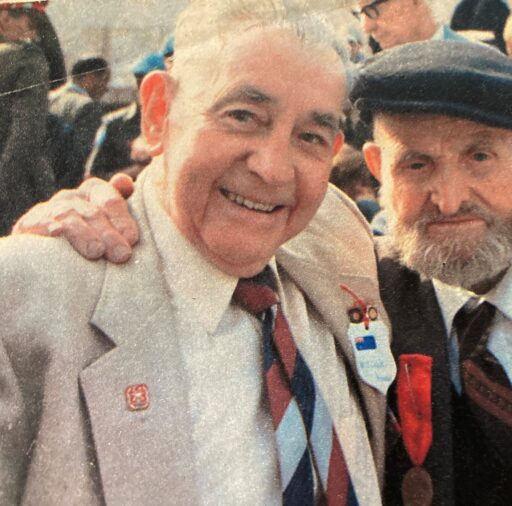

The psychological damage is perhaps best illustrated through Harold “Pompey” Elliot, commander of the 1st Brigade at Fromelles. He was haunted by the carnage he oversaw that night, having fiercely opposed the attack taking place. When it was over, he met with the survivors as they returned and then went to headquarters, “put his head in his hands and sobbed his heart out.”

He would return to Australia after the war and became heavily involved with the RSL, becoming President of Camberwell Sub-Branch and working tirelessly for the wellbeing of returned veterans. In 1931 he would take his own life, another victim of the carnage of Fromelles.

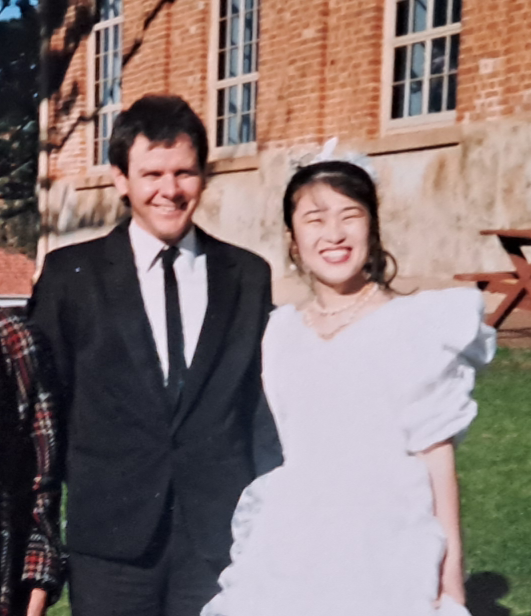

For my great grandfather, the psychological trauma was matched by a lifetime of pain from the metal fragments in his neck. Like Pompey Elliot he became a member of the RSL and found comfort in the mateship of fellow veterans. Cloaked in the ANZAC legend he married a woman who would become the family matriarch. She fell for the ANZAC hero and took him from the slums to the middle-class suburbs of Bentleigh where they would live together for more than sixty years raising children, with grandchildren and great grandchildren to follow.

But he never forgot the statistic of the “106 who turned up at roll call” wherever he was.

Decades after my Pa Jim told me these stories, I would become a lawyer assisting veterans make submissions to the Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide. Some of these veterans had returned from Afghanistan and many more had traumas from service at home or in Peacekeeping operations. I was struck how similar these men and women were to Pa Jim. Each had a particular moment that had become shorthand for their trauma.

The war had transformed Pa Jim for both good and bad. It had mentally and physically wrecked him but also given him a new identity and an escape from his past. His salvation lay in his family at home and his family at the Bentleigh RSL. The modern veteran is similarly transformed by their service and the role of the RSL is the same for them as it was for Pa Jim.

It is the place to find support from those who have walked in your shoes.

Do you have a personal story about your service or that of a family member like this one? Contact our storytelling team at me***@********om.au