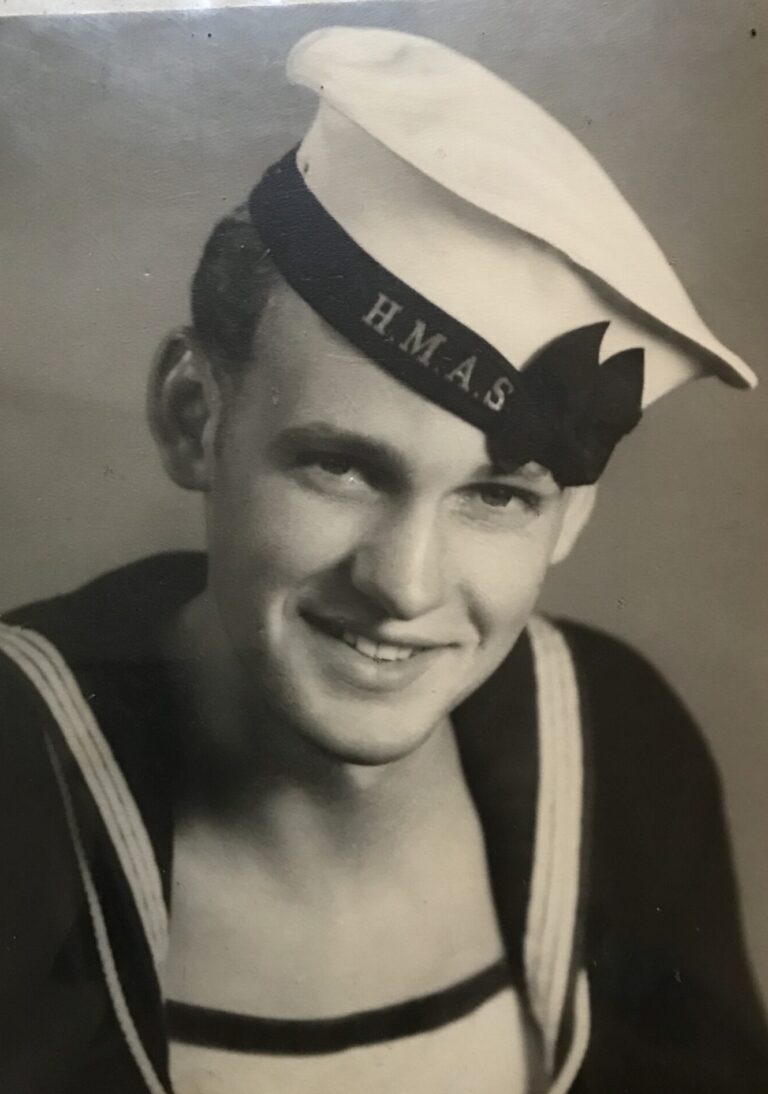

None are forgotten: the faces, names and stories that shaped a four-decade veteran

When Paul Fuller wears a poppy, he is reminded of the faces, names, and stories that have shaped his life.

And it has certainly been a life. Almost four decades of it spent in service across two armies: the Australian Defence Force and the British Army.

Paul is a master storyteller. And he tells stories with passion: about friends lost in service, soldiers he treated on the battlefield, and mates who never made it home.

Countless conflicts, two armies, one earth

During his 37 years of service, Paul witnessed the cost of conflict first-hand, from Northern Ireland to the Falklands, from Belize to America.

“I joined the Army in the UK as a boy soldier,” Paul recalls, “at 16 in the Parish Regiment. I went to Depot Para when I was 17. I passed out when I was just turned 18, then I went straight to Northern Ireland for 18 months.”

He understands the historical significance of the poppy as a symbol.

“The poppy, to me, from the perspective of being in two armies… it takes you back to the first World War, to Flanders Fields, to the Somme, to Passchendaele, to Gallipoli,” Paul explains.

But it also brings back memories from his personal experiences.

“I think of my best mate, who was just 18 when he was killed in Northern Ireland. I think of the blokes who died in the Falklands, some I knew extremely well.”

“Every death is felt, and none are forgotten.”

He remembers the comradeship, the humour in dark times, and the resilience of men and women who carried on despite unimaginable challenges. He also recalls the pain: the ramp ceremonies for the fallen, the soldiers he treated who didn’t survive, and the mates who later lost their lives to suicide.

“They wanted the adventure, the chance to travel to see something different. They wanted to go with their mates and experience something new. They went, they saw, they experienced horror, they experienced joy, they experienced laughter, larrikinism, fun, mateship, and the bond that these men had. They were like family. It’s a bond of brotherhood.”

For Paul, wearing a poppy is about remembering all of them: those who served, those who fell, and those still living with the scars of service.

“At the end of the day, the poppy resembles all the sacrifice, all the horror, and all the love that the soldier has for his friends that they’ve lost and the joy of those friends that they will live with until he passes. And those that are left, we honour them by wearing a poppy.”

“And on Remembrance Day, we’ll raise a glass. We’ll tell stories about them and their sacrifice, and their stories about their deeds, and the funny things that they got up to that made us laugh. And that is our best way of remembering them… wear this poppy with pride and honour those people.”

Not just when it’s convenient

Paul’s focus is on commemorating the past. But he also has a clear vision for now and in to the future: emphasising that veterans need support year-round, not just on commemorative days.

“Veterans aren’t just to be applauded on ANZAC Day or remembered when the Bugles play at 11:00 on Remembrance Day,” he explains.

“There are veterans out there living on the streets who are struggling with mental health, with alcohol problems, veterans who have lost limbs due to IEDs, due to diabetes, and they’re not entitled to things… because they don’t know what they’re entitled to.”

Organisations like the RSL need public donations to help veterans access support, including veterans who don’t know what support is available to them.

This November, when you buy and wear a poppy, you stand alongside Paul and thousands of other veterans. You honour their mates, their memories, and their families – and you help the RSL provide life-changing support to veterans in need.

Together We Remember.

The person behind my poppy

When I wear a poppy, I think of those who never returned. I served in two armies and lost many friends and colleagues. On my first tour of Northern Ireland, 20 young lads were killed. Some were close friends, including my best mate who had just turned 18. In the Falklands, I lost more mates, including a Kiwi serving in another company. My battalion lost 20, including attached arms, and my sister battalion lost another 23. All told, 255 servicemen and three islanders died.

I think of those lost in training accidents, in further tours of Northern Ireland, and men I knew killed in the Gulf and Bosnia. Many others I served with died in Afghanistan and Iraq. I remember the Canadians and Afghanis I treated—some survived, some did not—and the Australians we lost. I remember the ramp ceremonies that followed.

I think of the men and women I served with, in the ADF and the UK forces. I think of the wounded and of civilians who suffered through conflict. I think of the camaraderie, the humour, and the times when you had to dig deep.

I think of those who ended their lives. Too many of these I have known, including a young digger in Sydney who seemed to have everything to live for but took his life. I think of the widows and children left behind, often overlooked and forgotten.

Every death is felt, and none are forgotten. I think of survivors who showed the will to live when all hope seemed lost, and of the sacrifices of our forebears in North Africa, Singapore, Normandy, Arnhem, the Western Front, and Gallipoli. None are forgotten.

Paul Fuller