The double dispossession of Aboriginal veterans under the Soldier Settlement Scheme

When the Yoorook Justice Commission presented its final report to the Governor of Victoria, Margaret Gardener AC, on 1 July 2025 it included a recommendation to undo an injustice which affected hundreds, if not thousands, of First and Second World War Veterans and their families.

The recommendation called for an apology, support and redress for people affected by the Soldier Settlement scheme. The recommendation was built on a lifetime of campaigning by descendants of Aboriginal veterans.

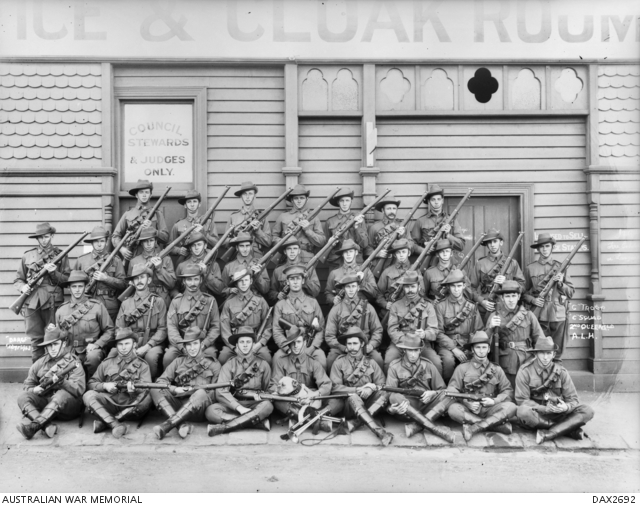

Among them was Uncle Johnny, a direct descendant of Herbert Lovett, one of five brothers who served in the First World War.

The Lovett brothers were born and raised at Lake Condah, a government run mission for the Gunditjmara people, who were known as the Fighting Gunditjmara, both for the guerilla war they fought against white settlers in the 19th century and their military service to Australia throughout the 20th.

In his submission to the Yoorook Justice Commission Uncle Johnny said that “my father and his brothers were the only brothers, black or white, to serve in both the First and Second World Wars and fight for the British Empire. They were the only group of brothers, black or white, to serve together in both World Wars.”

The brothers ages ranged between 18 and 35 years old when they enlisted in the First World War. They were to be part of some of the most infamous battles of the war.

The eldest brother, Alfred, fought at Pozieres which Charles Bean famously said was “a ridge more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on Earth.” Frederick Lovett served in Palestine with the 4th Light Horse Regiment in Palestine and Sinai and may have been part of the famed calvary charge at Beersheba.

Herbert Lovett, Uncle Johnny’s father, was a machine gunner on the Hindenburg Line.

“My father did not see a car until he was fifteen,” Uncle Johnny said. “Five years later he was operating a machine gun and seeing planes a lot bigger than bark canoes. It must have been something beyond his imagination.”

Officially Aboriginal Australians were not allowed to join the armed forces in the First World War as the racial restrictions of the Defence Act excluded “those of substantially non-European descent.” This was overlooked in the Lovett’s case after the recruiting officer deemed that they had enough white blood in their ancestry to qualify.

The Soldier Settlement Scheme had no such race-based restrictions.

The scheme was first established in 1917 with the Discharged Soldier Settlement Scheme Act 1917. The Act said that any person who served in the Australian armed forces could apply for land which would be provided under the provisions of the Closer Settlement Act. Veterans had to apply to a committee who would determine if the applicant “was suitable as a settler or may prove after training to be suitable”.

All five brothers made it back to Australia alive. When they returned to Lake Condah mission, they found it had been closed government, forcing them off the land of their birth. The brothers applied for land under the Soldier Settler scheme and were rejected.

“He was denied because he was an Aboriginal,” Uncle Johnny said of his father. “He was denied a life simply because somebody thought he didn’t matter, and other Aboriginals didn’t matter.”

It is believed only two Aboriginal veterans from Victoria were deemed suitable to be given land under the scheme and both were awarded land of such poor quality that it proved impossible to work as a farm.

Despite this four of the brothers volunteered again when the Second World War broke out and the fifth was told that, at 55, he was too old. The remaining four were joined in service by their younger brother Samuel who joined the 2/5th Battalion. The other four were too old to serve overseas but served in Australia, Herbert in the catering corps.

Their next generation, the sons and daughters of the Lovett brothers, also enlisted and served in the army and air force both in Australia and overseas.

Nigel Steel of the Imperial War Museum, speaking in a panel on the ABC’s Awaye program with Uncle Johnny Lovett, said he knew of no other family in the British Empire who matched the Lovett’s for military service.

When the Second World War was over Herbert Lovett again applied for land under the Soldier Settlement scheme, this time for the land of his birth at Lake Condah mission which was being carved up for returned soldiers. He wrote to the responsible minister:

“Dear Sir,

I am writing to you to see you could give me any information regarding the cutting up of Lake Condah Mission Station into blocks for Aboriginal Serviceman of this War. If same being made done, I would like to make an application for a block.”

He did not receive a reply. No Aboriginal veteran received a parcel of land at either the former Lake Condah or Coranderrk Aboriginal missions.

In 1946 Heywood RSL Sub-Branch wrote to the Minister of Lands asking that if the government cut up Lake Condah mission, they should give it to the Aboriginal servicemen “as we believe these men should be given the opportunity to settle down and reap the benefits due to them from a grateful country.”

The Minister of Lands responded that the matter would be investigated but “…it would be very difficult to set this area apart for allotment to one type of ex-serviceman only, but if the land is made available, applications received from eligible Aborigines and half-castes would be considered and dealt with on their merits.”

Again, no Aboriginal veteran would be granted any of the land from the former Aboriginal missions at Lake Condah or Coranderrk.

The story of the Lovett family was far from unique.

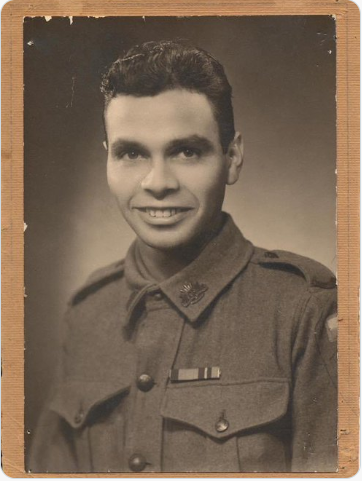

Another family affected by the scheme was that of John Stewart Murray, known by his second name Stewart, who would go on to be a prominent Aboriginal activist after the war.

“My father enlisted in the Australian army in 1941,” his son, Gary Murray, said. “Behind the captain registering him there was a cartoon which had two donkeys pulling a cart in opposite directions. Beneath the picture was a caption that read “If they pulled together, they would get it moving.”

The message of the cartoon resonated with Stewart throughout his time in the army.

Born in Lake Boga, Victoria, his tribal name was Werremander which means “Whistling Spear”, a name which Gary believes characterised the man.

Stewart Murray served in New Guinea and Borneo and proved his commitment and courage time and time again, rising to the rank of Lance Corporal by the end of the war.

“He always volunteered to be on point duty,” Gary Murray said. “That was the most dangerous position, you would be spotted first and killed by a Japanese ambush.”

Despite the hardships of the war Stewart Murray found that the message of the two donkeys pulling in opposite directions was well learnt in the army.

“It was the first time in his life where he felt like he was an equal,” Gary said. “He was working together with his white comrades and nobody cared about the colour of his skin. But that equality all ended when he came home.”

When he arrived home in Australia Stewart Murray returned to his ancestral home at Lake Boga and made three applications for land under the soldier settlement scheme.

“It was a double dispossession,” Gary Murray said. “Not only were the Aboriginal veterans denied land under the scheme, the small amount of land left to Aboriginal people on missions was given over to white veterans.”

Gary Murray says his father received no support from the RSL when he returned to Australia and at first struggled to make ends meet on unemployment benefits. His applications for soldier settlement land were turned down time and time again.

He married in 1948 and moved to a property his father leased in Balranald, mainly labouring and fixing up fences. When the property was flooded, he was forced to move to Melbourne and managed to get a housing commission house in Glenroy.

“He didn’t drink, and he didn’t smoke,” Gary Murray said. “There were eight of us kids living in the concrete housing commission house in Glenroy, but my father worked hard and bought the house off the housing commission.”

Stewart Murray became a leading Aboriginal activist and was a founding member of the Aboriginal Advancement League, helped found the Fitzroy Legal Service, served on the State and National Tribal Councils and was appointed to the Victorian Aboriginal Land Council.

Despite not being involved with the RSL he never forgot his fellow Aboriginal veterans and fought for their service to be better recognised.

In 1985 as Acting chair of the Aboriginal and Islanders Ex-Serviceman Club he clashed with then RSL Victoria President Bruce Ruxton who was opposed to Aboriginal veterans marching together on ANZAC day.

“They cannot march alone,” Bruce Ruxton told the Canberra Times. “This is the same whether they’re black, white or brindle. The rules are the rules.”

The Anzac Day Memorial Council voted against the Aboriginal veterans being allowed to march together but Stewart Murray decided to stage their own Anzac Day March instead.

“All people are welcome – we won’t discriminate” Stewart told the Canberra Times.

On ANZAC Day 1985 around 100 veterans marched through High Street Northcote to the local RSL at the same time as the traditional march.

“Despite what happened I ended up changing my mind about Bruce Ruxton,” Gary Murray said. “He spoke well at my father’s state funeral. He said the war had knocked ten years off my father’s life. My father was in his sixties when he died, didn’t drink or smoke, so Bruce was probably right. My mother had trouble getting a war widows pension, but Bruce Ruxton stepped in and made sure she got it.”

For the Lovett family the rejection of their claims for soldier settlements did not change their commitment to the Australian armed forces. They continued to volunteer with each passing generation. Descendants of the Lovett brothers have fought in every conflict involving Australia, including Korea, Vietnam, East Timor and Afghanistan.

While the numbers of Aboriginal people serving in the Australian armed forces have continued to grow, recognition of that service has been slow to come.

In 2006 Healesville RSL Sub-Branch worked with Aboriginal Elder Aunty Dot Peters AM, the daughter of a Second World War POW, to found the Victorian Aboriginal Remembrance Service. In 2007 the Indigenous service moved permanently to the Shine of Remembrance and the Aboriginal flag was raised there for the first time.

In 2017 Ricky Morris, the 25th member of the Lovett family to join the Australian defence forces, was one of 12 Indigenous Australians chosen to take part in the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Beersheba. Ricky is a veteran of East Timor and Afghanistan and the grandson of Frederick Lovett who served with the 4th Light Horse.

Also, in 2017 the dream of Stewart Murray was finally realised when Aboriginal veterans marched together at the head of the ANZAC Day March in Canberra.

In 2021, during the COVID lockdowns, Welcome to Country was performed during Remembrance Day service at the Shrine of Remembrance and the following year became a permanent part of the Anzac Day dawn service.

The ceremony is a small step in recognising the service of the thousands of Aboriginal Australians who have served in the countries defence forces. There are many more steps to take to reconcile with some of the injustices they faced on their return.

RSL Victoria Chief Executive, Sue Cattermole, has welcomed the recommendations of the Yoorook Justice Commission.

“There is no doubt that Aboriginal Australians, particularly in Victoria, have made an outstanding contribution to the Australian Defence Forces, even before they were officially citizens of the country,” Sue Cattermole said. “The RSL urges the Victorian government to address the injustices faced by Aboriginal servicemen and women, particularly around the denial of land under the Soldier Settlement scheme.”

The Victorian government is still considering the recommendations of the Yoorook Justice Commission.

Photo: Herbert Lovett

Above left: Alfred Lovett with wife Sarah and sons Alfred Patrick and Leo Lawrence in 1915. Both Alfred and Leo would later serve in the Second World War. (Australian War Memorial P01651.001)

Above right: John Stewart Murray during his Second World War Service